the forgotten hand

a brief history of Catholic almsgiving and the rise of anti-empathy

“Whatever you did for the least of my brethren, you did unto me.”

(Matthew 25:40)

The Catholic Church has always been a faith of doing. Before it became the massive institution that it is today, with its cathedrals and conclaves, it was a community of action — feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, tending to the sick. Monks founded the first hospitals, nuns opened schools and orphanages for children forgotten by the rest of the world. Dorothy Day built houses of hospitality in the midst of the Great Depression. For centuries, being Catholic meant showing up for people who were suffering. Not because it was politically fashionable, but because it is so deeply ingrained in the religion.

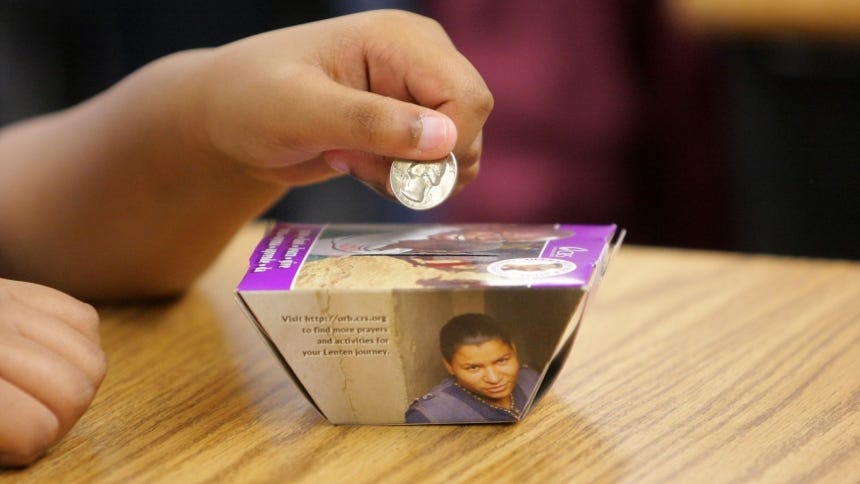

And yet, lately something feels very off, for lack of a better word. In some conservative corners of the Church empathy, the simple act of feeling with someone, has been deemed a liability. Certain politicians (names redacted) have even called it a sin. Their persuasion is that compassion can blur moral boundaries, that feeling too deeply for a sinner means condoning their “sin”. But for a faith quite literally founded on mercy, that framing seems like a contradiction to the rich history and doctrine of the faith itself. I spent thirteen years of my life collecting loose change in a paper rice bowl to donate to the less fortunate during Lent. I sang songs about how Jesus loves all of His children. Today, I still carry loose dollars in my pockets in case I come across kids fundraising for an animal shelter or someone who is just down on their luck and hungry. But my attempts at religious adherence are viewed by many as a moral weakness.

This shift stands in stark contradiction to Catholic teaching. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (our Constitution, kind of) is clear:

“Social justice can be obtained only in respecting the transcendent dignity of man. The person represents the ultimate end of society.” (CCC 1929)

In simpler terms, people come first.

Scripture says the same. James writes, “If a brother or sister is poorly clothed and lacking in daily food, and one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace, be warm and filled,’ without giving them the things they need, what good is that?” (James 2:15-16). From the beginning, Christian love in action has encompassed all aspects of social justice. Not just preaching about it, but being actively involved in it. So often, we view “social justice” as a purely secular term, when it’s actually baked into the Church’s DNA. Catholics picketed for workers’ rights and were important in the abolition movement. The notion that we should be a voice and a helping hand for the least among us is not new nor is it unorthodox.

Over time, these acts of love became institutions. Monastic communities transformed their compassion into physical structures when they founded hospitals, hospices, orphanages, and schools. In 1981, then Pope Leo XIII released Rerum Novarum, a response to industrial capitalism’s exploitation of workers. He argued that defending fair wages and protections in the workplace wasn’t political, but spiritual. Later popes followed his lead, most notably Pius XI’s Quadragesimo Anno (1931) and John XXIII’s Mater et Magistra (1961). Both of these built on the same legacy that linked faith with justice.

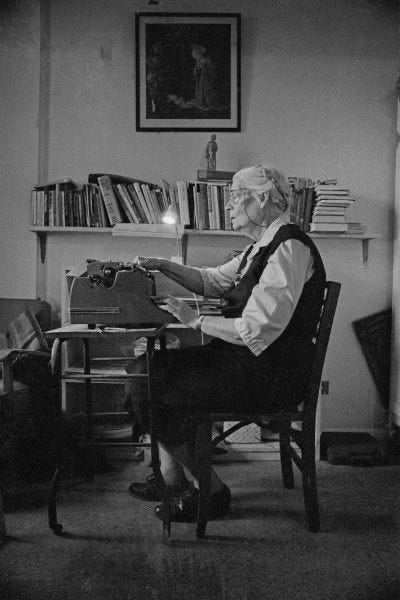

Dorothy Day, one of my favorite Catholic figures, carried that torch into the modern world. She co-founded the Catholic Workers Movement, serving soup to the poor and writing essays against war and corporate greed. At her time, she was a controversial figure — too devoutly religious to be secularly progressive, yet too progressive for the growing conservative voices in the Church. She was called a socialist for her liberal views and her frequenting of the party scene made her unpopular with the staunch religious crowd. But her brand of holiness wasn’t docile, it was radical. She challenged people to create a better world by caring for the communities around them. In all her life, she never capitulated to any narrative that claimed empathy equates to weakness. Dorothy lived through two World Wars, an economic depression, the Civil Rights Movement, and many social and political shifts. Through all of this, her position was clear:

“We cannot love God unless we love each other, and to love we must know each other.”

-Dorothy Day

Catholics have historically stood at the heart of social reform, even when it put them at odds with those in power. During the 19th century, Catholic abolitionists in the United States worked alongside Quakers and Protestants to fight for an end to the slave trade. Religious orders like the Sisters of Charity and Jesuits (Pope Francis’s order) gave food and lodging to people escaping slavery in the Confederate South. In 1839’s “In Supremo Apostolatus”, Pope Gregory XVI formally condemned the slave trade, twenty-six years before it was abolished in the United States. He wrote, “…no one may unjustly reduce another to servitude.” While it is true that not every Catholic community shared that sentiment, the Church’s stance created the framework for a theology of freedom that would echo later in the Civil Rights era. This proves that at its best, the Catholic Church stands against cruelty as a byproduct of profit.

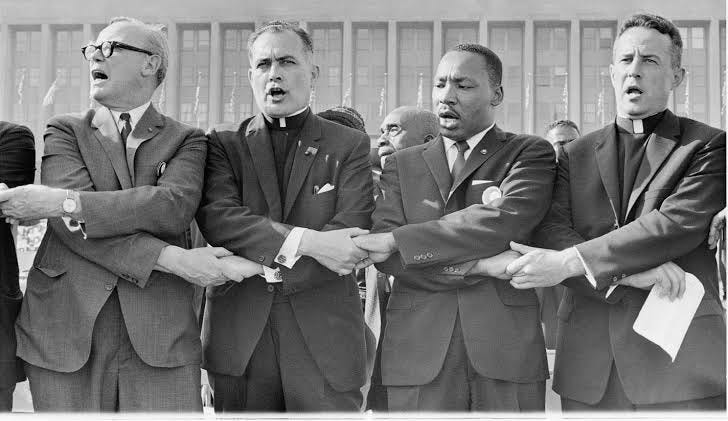

Throughout American history, Catholics have quietly led social reform. Religious sisters built hospitals that now form the backbone of our nonprofit healthcare system. Priests and nuns marched at Selma with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The U.S. Bishops’ 1979 letter, “Brothers and Sisters to Us”, denounced racism as, “a sin that divided the human family”. More recently, the late Pope Francis’s “Laudato Si” (2015) named climate action and care for the poor as inseparable responsibilities. The Catholic Church teaches that believers must care for their communities as well as the world at large.

This has always been the Church’s vision. It is not an ideology, but a way of living out mercy. The Catechism calls these the “Corporal Works of Mercy”. We are instructed to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, visit the imprisoned, shelter the homeless (CCC 2447). These aren’t side projects to be completed when there is enough time. They are the faith in action. And they extend to those who may not believe what we believe in or think how we think.

That’s why the new suspicion towards empathy feels so unnerving. A 2022 PBS NewsHour report described a growing movement among conservative Christians who claim that empathy “leads people away from the truth”. They believe that to feel with others means to excuse their sins. That compassion must be filtered through a moral litmus test. They embrace a theology of mercy with caveats. While it is true that Gen Z is more likely to attend weekly church services than their Millennial predecessors, it is also true that these new church attendees are more likely to uphold right wing beliefs. The new nationalistic, exclusive voices are shouting over doctrine and Scripture that calls on us to love our neighbor unconditionally.

“Blessed are the merciful, for mercy shall be theirs”

(Matthew 5:7)

“Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful”

(Luke 6:36)

To call empathy sinful is to willfully misunderstand the very premise of Christianity. God’s defining act was one of empathy: becoming human, sacrificing His son for the salvation of humanity. True Christian love — not the kind that is limited and conditional — is what brought me back to the Church, and it is the reason I have stayed. Over the past year, I have watched the Catholic community in Chicago stand against an administration that is antithetical to the compassion and almsgiving that is at the core of their faith. Priests have marched alongside protestors to ICE detention facilities and brought Communion to the homes of immigrants who cannot come to Mass due to fear of deportation. Pope Leo recently addressed the Church’s stance on the sanctity of life saying that he is unsure whether someone who is against abortion but hardens their hearts to immigrants is truly pro-life. The Gospel doesn’t tell us to ration our mercy. It is not a limited resource. It commands us to love, even when it’s inconvenient or uncomfortable.

This doesn’t just apply to people we like. In fact, the true test of empathy is how we treat people we can’t stand. When news broke of far-right podcaster Charlie Kirk’s death, social media erupted with celebratory posts. At his funeral ( yes, the one with the pyrotechnics and merch), Donald Trump said, “I hate my opponent…I don’t want the best for them.” Both reactions, though politically opposite, reflect the same spiritual corrosion — the idea that compassion should have limits. This does not go to say that I remotely support any of Charlie Kirk’s rhetoric or that I entertain those I deeply disagree with. I think that Kirk’s platform was hateful, dangerous, and antithetical to the teachings of Christ. I’m not sure whether the world was a better, kinder place because he was in it. But I also want the best for my opponents. I don’t think anyone should be shot, regardless of their beliefs. And I don’t think this should be an unpopular opinion. Holding this belief does not change the legacy of a person, rather it acknowledges their humanity even if they did not acknowledge mine. And Jesus’ command to “…love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44) wasn’t conditional. Wanting the best for people we disagree with isn’t weakness, it’s discipleship. For anyone on any point of the ideological spectrum to wish suffering on another, or to find joy in their downfall, is the exact inversion of Christianity’s message.

Learning to have empathy has deepened and enriched my understanding of the world. Anyone who knows me knows that I can hold a grudge. I’m judgmental and intolerant towards people I disagree with. But empathy means seeing the humanity in everyone I interact with — seeing them as a person before an ideology. Now, I take a greater interest in how people developed certain beliefs rather than why they continue to hold them. The way I see it, the majority of my opponents are not bad people, just misled. In order to engage in productive dialogue, you need to have some degree of respect for who is standing across from you. And in order to have respect for them, you need to be able to see them as a person. Catholics believe that Jesus sacrificed his own life for us not because we were perfect, but because we were lovable. Love doesn’t ask who you voted for before helping you unload your groceries from your car. It doesn’t ask what God you believe in or what language you speak before comforting you after the death of a parent.

So why the backlash? I think part of it comes from fear that empathy will slide into moral relativism. Part of it is the increasing politicization of “social justice” as a term. It has been co-opted, polarized, and made out to be something negative. We also deal with media fatigue. When every headline, emergency alert, and Instagram post is a reminder of the broken system we live in, it’s easy to isolate and distance yourself from it all. Compassion during times of crisis seems like a bottomless demand, especially when we’re all hurting. Blue states are subject to ICE raids and the deployment of armed troops. Just this morning, I woke up to a notification that families were tear gassed on their way to a Halloween parade in the neighborhood I used to live in. Red states do not fare much better. This week, it was announced that SNAP and WIC benefits would not be paid out come November 1 due to the ongoing government shutdown. One in every eight Americans will go hungry during the holidays, with residents of Republican leaning states being disproportionately affected. Having a scapegoat allows us to channel our hurt into anger, even if just for a moment. We point fingers and retreat back into doctrine because that feels safer than staying open to suffering.

But this retreat comes at a cost. The Church’s strength has never been in moral superiority, but rather in its mercy. Hospitals, schools, and relief organizations were not founded by people obsessed with being right — they were founded by people whose love didn’t come with conditions. A Church that denounces empathy risks losing its credibility and even worse, its soul. The Catechism is blunt on this point too:

“Love for the poor is incompatible with immoderate love of riches or their selfish use.”

(CCC 2445)

Mercy and almsgiving aren’t a distraction from the truth. They are truth in motion. A Church without empathy might look tidy, but it will also be empty and cold.

This has been on my mind a lot lately — how easy it is to love in theory and how exhausting it can be in practice. I’ve written this entire essay and spoken what I know to be true, but tomorrow it is likely that I get into an argument with someone on Threads or call my opponent stupid. It’s simple to donate to a cause or post a GoFundMe link, but it’s much harder to love the person who votes against my rights or uses faith as a weapon. It’s even harder when embracing empathy feels like accepting an invitation to pain. But I think that’s the point, to feel human rather than feel comfortable.

Faith, to me, has never been about purity or perfection. At least for the entirety of my adult life. How could it be? I’m far from having the perfect track record. Instead, I think faith is more about proximity. Being close enough to people’s pain that it makes you feel something. If I can believe that Jesus met lepers and tax collectors with an open heart, then the least I can do is fight against the urge to harden my own. Empathy doesn’t erase truth, it amplifies it. And if to be merciful is to be Christlike, then to withhold it is the most certain way to forget who we are and the tradition we come from.

Further Reading and Sources

Catechism of the Catholic Church: 1929,2445,2447

Rerum Novarum (1891) — Pope Leo XIII

Quadragesimo Anno (1931) — Pope Pius XI

Mater et Magistra (1961) — Pope John XXIII

In Supremo Apostolatus (1839) — Pope Gregory XVI

Brothers and Sisters to Us (1979) — U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops

Laudato Si’ (2015) — Pope Francis

Separation of Church and Hate — John Fugelsang

PBS NewsHour: “Is empathy a sin? Some conservative Christians argue it can be.” (2022)